Male Destruction of the Earth System

We are delighted to feature a series of six articles by the distinguished Professor Dr. Yukio Kamino, a Resource Person at OISCA International. OISCA is a Japanese NGO that strives to foster Life on Earth. Professor Kamino has an extensive background in social sciences, humanities, and metaphysics, and has devoted many years to tackling issues of sustainable development and environmental education. He has authored numerous publications and has been instrumental in advancing global efforts to enhance ecological sustainability.

In this series, Professor Kamino will explore the idea of ecofeminism and how it can help us create a more sustainable future by integrating feminist values with ecological principles. We are grateful for his generous contribution of wisdom and experience to our readers, and we hope that these articles will spark constructive dialogues and motivate positive actions toward a more fair and inclusive world. This is the third article in the six-part series by Dr. Yukio Kamino.

The last part of this series illustrated the millennia of patriarchal discrimination and oppression against females, and d’Eaubonne’s ability to persuasively transmit that reality through Le féminisme ou la mort (1974) that is translated into English a half-century later as Feminism or Death (1974/2022). Believing the most profound contribution by her was synthesizing Ecology and Feminism, this chapter shifts its focus from her feminist writing to an intellectually transcendent stage where her creative mind blossomed to connect these two subjects, as symbolized by forging the term ‘ecofeminism.’

According to d’Eaubonne, by 1970 ecological issues had emerged as a major concern of some elite circles of the USA, who started to look beyond the current issues to envision the ecological issues for the coming future. She noted, for instance:

In January 1970, President Richard Nixon devoted a large part of his State of the Union Address to the ecological question. Soon after, a law was passed ordering the airlines to devise a plan by 1972 that would reduce the fumes from combustion by three-quarters (1974/2022, p. 198). Consider, however, this remark: “Ecology is going to replace Vietnam among the essential preoccupations for students.” Who said this, and when? The New York Times…in 1970” (1974/2022, p. 197).

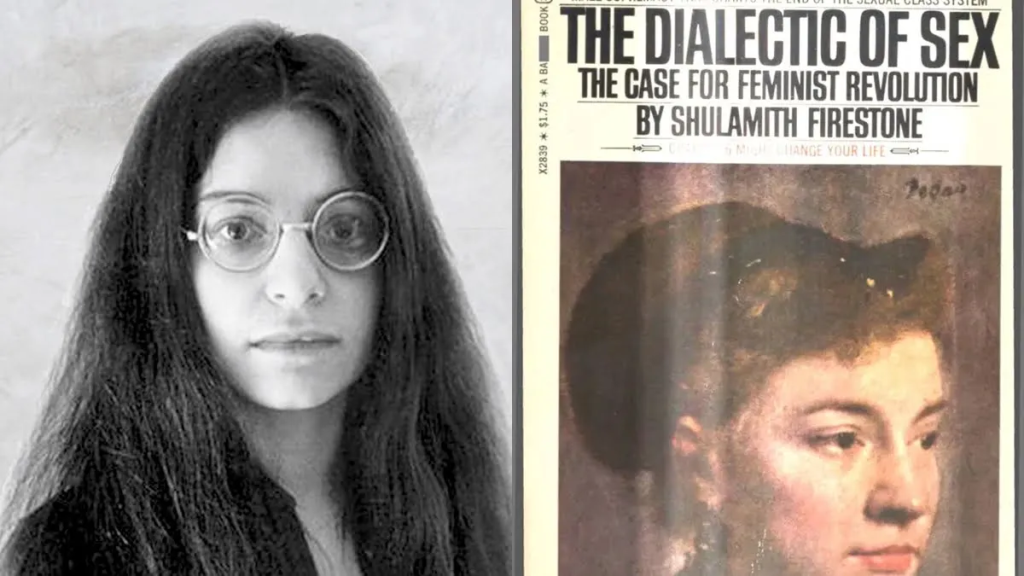

As for the connection between Ecology and Feminism, d’Eaubonne (1974/2022) acknowledged that in 1970 “Shulamith Firestone had already alluded to the ecological content inherent in feminism in The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution” (p. 190). However, that work did not jump-start ecological feminism: “This idea had remained at the embryo stage until 1973” (p. 190).

Before reading Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex, d’Eaubonne herself “defended this [ecological feminist] point of view…in 1972, in a letter to Nouvel Observateur, after an ecological conference where the absence of women was particularly blatant” (p. 196). The minority feminists stimulated by Firestone (1970) and led by d’Eaubonne “founded an information center: the ‘Ecology-Feminist Center,’ destined to become later, as a part of their project of melding an analysis of and the launching of a new action,

ecofeminism” (p. 190).

Yet, the general French public and most feminists largely neglected this emergent ecological feminism as they remained focused on the contemporary intra-human affairs as they had been led traditionally; to them, the planetary ecological integrity must have been too remote an issue to study and act upon.

In 1974, d’Eaubonne expressed her disappointment with the prevalent inclination of French society in which the great majority, including some ‘intellectuals,’ paid little attention to the scientific alarms on the imminent crisis caused by the anthropogenic transformation of the Earth System. But is worldwide catastrophe really at our doorstep? Stopping short of the noble remarks of somebody like Jean Lartéguy [1920-2011; a French writer, and journalist], who, faced with figures I was citing on television, shrugged his shoulders and said, “Oh, specialists are always mistaken in their predictions…”

A lot of people say, “Someone will invent something” (1974/2022, p. 196). Ecofeminists could not attain much support from the traditional feminist community as well. Conventional feminists were still reluctant to transcend their traditional focus on achieving inter-gender equality in their lifetime. In other words, their vision was narrow in both Space (their society, not Earth System) and Time (their own life, not that of the coming generations). Faced with these realities, d’Eaubonne took it her mission to broaden the vision of the narrowly focused conventional feminists. She stated in “Introduction” of the original Feminism or Death:

[I]t seems necessary in 1974…to consider the question [of feminism] with a little more distance and, at the same time, undoubtedly, with a feeling of urgency much more searing than in 1970. It is an issue, given the recent revelation of the futurologists, to consider feminism from a much vaster plane than the one envisaged to this point, and to seek how the modern crisis of the battle of sexes is tied to a mutation of the totality—indeed, of a new humanism, the only possible salvation” (D’Eaubonne, 1974/2022, p. 3).

While d’Eaubonne fully agreed with the conventional feminists that women had been unjustly devalued by men, and their society needed to be reinvented urgently to abolish the existing patriarchal institutions and practices, the most important mission of feminism that she envisioned was uniquely transcendent. While the Means remained as they had been—to defeat Patriarchy—the End must expand to incorporate keeping the healthy ecosphere as a whole in which humankind had emerged and on which it still depends for survival.

It seems that the time has come to show that feminism is not solely…the protests of the human category that has been crushed and exploited from the most ancient times, since “woman was a slave before slavery existed”… Feminism is [to save the] entire humanity in crisis; it is [for] the reinvention of species; it is truly the world that will change its base [from the patriarchal world order]. And much more still: there is no longer any other choice; if the world refuses this mutation that will surpass all revolutions…it is condemned to death—and to death extremely imminent (D’Eaubonne, 1974/2022, p. 4).

In the section headlined “For a Planetary Feminist Manifesto,” d’Eaubonne (1974/2022) underlined the same point: “The feminist combat, today, can no longer limit itself to the abstract ‘equality of the sexes’… At present, it is an issue of LIFE OR DEATH” (p. 98; capitalization original).

The most essential objective of feminism is no longer the promotion of the rights and dignity of females or ‘equality of the sexes,.’ Because even a society with perfect inter-gender equality cannot survive without the functional integrity of the Earth System. Yet, d’Eaubonne continued to be a ‘feminist in strategy. ’She upheld traditional feminism’s search for rights and dignity because she was convinced that a livable Earth System required the abolishment of the existing human system—Patriarchy.

The man in the patriarchal system is…first and foremost, responsible for the insane birth rate, just as he is for the destruction of the environment and for accelerated pollution that coincides with this insanity to render a planet unlivable for what prolongs it (D’Eaubonne, 1974/2022, p. 85).

These 1974 visions of a “patriarchal system” and “planet unlivable” were fully affirmed a half-century later by Bahaffou and Gorechi (2020/2022) in their “Introduction to the New French Edition.”

Along with Françoise d’Eaubonne, we uphold the value of this work’s title, and we reaffirm: from now on, it’s feminism or death! In using this phrase, the author signaled the urgent need for recognizing the patriarchal nature of the widespread murder of living things. Without that understanding, and without setting in motion a radical turn toward ecofeminism, what awaits us is death” (p. xvii).

They further confirmed d’Eaubonne’s belief in the patriarchal nature of the escalating ecological devastation by criticizing male-produced capitalism and questioning the legitimacy of the term ‘Anthropocene,’ which has gained much currency among ecologically attentive world citizens in this 21st century. Bahaffou and Gorechi (2020/2022) point out that the drastic transformation of the Earth System, such as Global Warming, has been caused by Patriarchy.

[W]e are experiencing global warming; this is rather a historic turning point during which, for the first time, “exploiters at the top have chosen [profit] over their own lives.” As for the concept of the “Anthropocene,” which suggests a collective responsibility for the deterioration of Earth, we prefer to speak to the “androcene” (andro meaning “man”): if ecosystems are destroyed, if climate refugees around, if the sixth mass extinction is underway, it is not the fault of generalized humanity but that of a small group of rulers and patriarchal-capitalist societies who accelerated it” (p. xviii; square brackets original). Like Bahaffou and Gorechi (2020/2022), many contemporary ecofeminists fully agree with the perspective advanced by d’Eaubonne in the mid-1970s that the ‘male civilization’ has been the essential cause for today’s deepening ecological catastrophe.

Dr. Kamino is a graduate of Keio University and studied social sciences, humanities, and metaphysics in the USA. He focuses on sustainable development and environmental education and has authored books on ecological sustainability. He worked as a Senior Researcher and Coordinator at OISCA International until 2019. He is now engaged with them as a Resource Person.