Augusta Savage: Sculpting a Legacy of Art and Activism

“I was a Leap Year baby, and it seems to me that I have been leaping ever since.” -Augusta Savage (1892–1962)

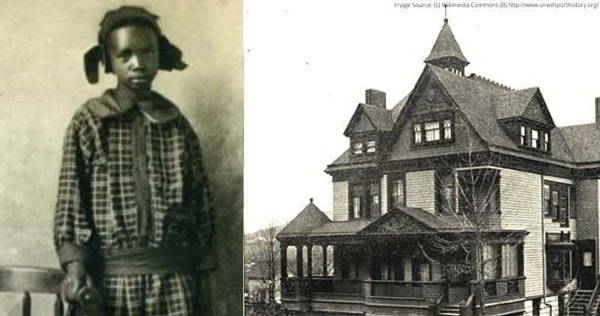

Augusta Savage was a prominent African American sculptor and influential figure in the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural and artistic movement that emerged in the 1920s. Born on February 29, 1892, as Augusta Christine Fells in Green Cove Springs, Florida, Savage faced numerous challenges as a black woman pursuing a career in the arts during a time of racial and gender discrimination.

The child of Edward Fells, a laborer and methodist minister, and Cornelia Murphy, Augusta developed a love for art at an early age. Green Cove Springs, Florida is located just South of Jacksonville on the bank of St. John’s River, which is full of natural red clay. Her father was a methodist preacher, who believed sculpting was a sin because it created images. As a result of his beliefs, Augusta received constant scolding and whooping from her father. Augusta grew up in a poor family with 13 brothers and sisters as she had no toys to play with, she loved to spend time in her backyard where the soil was rich in natural clay. This was where she learned to make miniature animals.

At 15 she married John T Moore in 1907 and had her only child Irene in 1908. After Moore died a few years later, Augusta moved to West Palm Beach in 1915. She moved to West Palm Beach due to a position her father received. She had picked up teaching even though she was still a student. She taught clay modeling at the school. The superintendent encouraged her to exhibit her clay. In 1915, she married James Savage, a carpenter, for the second time until her divorce in the 1920s. But she kept his name. She did not let troubles in her personal life affect her passion for sculpting. She thrived artistically in West Palm Beach, receiving local encouragement and prizes.

Her keen interest helped her to make a decent amount of figurines, which she put up for display at the West Palm Beach County Fair, where she won a $25 prize for the most original work. She moved to Jacksonville Florida, hoping to make a living by executing commission busts of the city’s well-to-do. But when that plan failed, she began attending Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College. She won first prize for her sculpture at the county fair. The commissioner recommended her to study sculpting in New York City at the Cooper Union, a private art college. She left her daughter with her parents in Florida and moved to New York City to study art. It was because of her winnings that she dared to move.

Augusta thrived there and also received a scholarship. She completed a 4-year program in 3 years. Her name and fame spread fast and she found herself making bust off many honorable Afro-American leaders. Augusta obtained her first commission for making a bust for the Harlem library. Her outstanding sculpture brought many commissions, including one for a bust of Marcus Garvey. She earned praise for depicting people more humanely. They were empowering, they were lifelike.

She later found support from her father also, when she sculpted the Virgin Mary and other religious figures. In 1923 Augusta married for the third time, but her husband died the next year due to pneumonia. In 1920, she moved to Harlem, a prominent African American neighborhood in New York City. At that time, the community was experiencing an exciting boom in the arts, known as the Harlem Renaissance and Augusta was a part of it.

Savage received a French scholarship in 1922. But the offer was taken back when white Alabama students who had received similar grants refused to travel to France unless she was removed from the group with a grant from the Carnegie Foundation. After being denied entry, Augusta used the local newspaper to make the irrational decision known to all. But it didn’t sway the committee members. Life was marked by personal tragedy. Her father became paralyzed and her family home was destroyed by the hurricane. All of them moved to New York City with her.

In 1928 her sculpture, the head of negro, known as Gamin, made it to the cover of Opportunity Magazine. It also won her International fame and recognition. She was later given a scholarship to study in France. Her dream of studying with great artists and sculptures came true but she was more self-taught. She toured the whole of Europe. She went to France, Belgium, and Germany to research sculptures in cathedrals and museums. While in Europe, she learned traditional cultural techniques in bronze sculpting, where you take the clay, make models, and cast them in bronze. She got laurels for her work everywhere.

Augusta returned to the US in 1931 amid the Great Depression. During the depression, art sales became non-existent, it gave Savage time to focus on something else and created a sense of community. She found work as a teacher and made a bust for Frederick Burgess, and James Johnson. The Savage School of Arts was the largest program of free classes in New York in 1932. She was appointed in 1936 as an assistant supervisor in the federal arts project, a division of the Works Progress Administration. She fought for the commission for black artists and to have African American history included in public murals. She was the first black woman to be elected to the National Association of Women’s Sculptures. She opened her art studio in Harlem, New York. It was the playground for many renowned black artists. She was also commissioned by the Board of Design New York. Eventually, the studio evolved into the Harlem community center. She provided opportunities that she never got in her life.

She was one of the four women and only two Afro-American commissions to create art for the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City. She created a work called Lift Every Voice and Sing, also known as The Harp. It was based on a line from the song by James Weldon and Rosamond Johnson. It was made of plaster and measured at 16 feet tall. The heart-shaped piece was made up of a choir of 12 extremely popular young people. The sculpture reimagines the heart with black singers as its strings. It was one of the highly viewed pieces at the World Fair and was photographed more than any other piece there. She did not have the funds to cast it in bronze, so it was destroyed. Once the fair ended, it was only because of the photographs and small reproductions that modern viewers could enjoy it.

Sadly, after returning from the Fair, Savage discovered that a position at the Harlem Center was given to someone else. She resigned in 1939 and opened a salon of contemporary negro art in Harlem, which was America’s first gallery for the exhibition, and sale of works by African American artists work. Later World War II cut all federal funding to art. She was forced to close the center and move to a small town. After the 1940s, she retreated to a farm South of Albany, where she taught art, held summer camps, and even did some writing. After becoming ill, she moved to New York City to be with her daughter.

Augusta understood her platform and that she needed to speak both with her hands and voice about the rampant racism. At that time, she was very outspoken about how artists and critics labeled black art as negro art. She also believed that the white artist community lacked respect for black artists.

Her sculptures weren’t just visually captivating but carried a greater meaning. She was a committed advocate for civil rights. Her art served as a platform to address the racial and social issues of her time. She was also the Director of the Harlem Community Center. Through her leadership roles in art schools and institutions, she was a mentor for the next generation of black artists.

Despite her artistic success, she struggled with finances and racism until late in life. But she always found a way out of it. Unfortunately, many of her works were never cast in durable materials and were later lost or destroyed.

Augusta openly fought racial prejudice in the art world and was labeled a troublemaker. She said that she was standing up not only for herself but for the future of people of color. She dedicated much of her life to teaching and encouraging young people to pursue artistic passion. Despite her artistic success, she struggled with finances and racism until late in her life. But she always found a way to keep making art. She is an inspiration to anyone who faces inequality and adversity. She always found teaching to be of more importance than creating art. She said, “If I can inspire one of these youngsters to develop a talent I know they possess then my monument will be in their work.”

Augusta Savage’s legacy extends beyond her artistic achievements; she remains a symbol of resilience and perseverance, breaking barriers in a time when opportunities for black artists were limited. Her contributions to the arts and her commitment to promoting diversity and inclusion continue to inspire generations of artists and activists.

–Nidhi Raj is an independent writing professional, storyteller, and mother with a keen interest in women’s issues and International Relations.

/shethepeople/media/media_files/9DrYNvAKdOPMunBzeNfd.png)